So, imagine my delight when I discovered that the Gala Dinner at this year’s Crime Writers Association (CWA) conference in York was to be held in the highly unusual venue of the cobbled Victorian Street in the Castle Museum. While we dined, we were surrounded by rows of recreated Victorian shops, including a chemist with a glistening array of poisons in jars behind the counter and a police station complete with a prison cell.

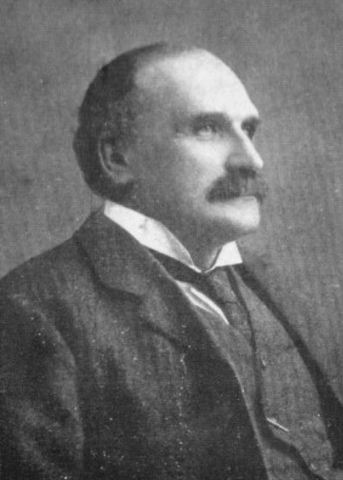

Unbelievably, the bulk of the exhibits at the Castle Museum were collected by one man, Dr John Kirk.

Dr Kirk had a medical practise in Malton. He was fascinated by history, and by vanishing ways of life – especially rural life. He realised that many old traditions and ways of working were changing forever. Acutely conscious that some trade skills were becoming obsolete he started to collect archaic work tools and other rare survivals of these endangered ways of life. He filled his home with bygones, his collection growing year on year. Sometimes Kirk accepted objects in lieu of payment for his medical services.

By the 1930s, his vast collection had outgrown his home. It included everything from perambulators and children’s toys to antique weapons, potato dribblers to a Tudor barge and Victorian hypodermic needles to horse bridles. Larger items included whole Victorian shop fronts, a hansom cab and a stuffed horse.

Determined to find a permanent and publicly accessible home for his vast and rare collection, Dr Kirk approached York Corporation who gave him the disused female prison in the centre of the city for his museum and helped modify it, so it was fit for purpose.

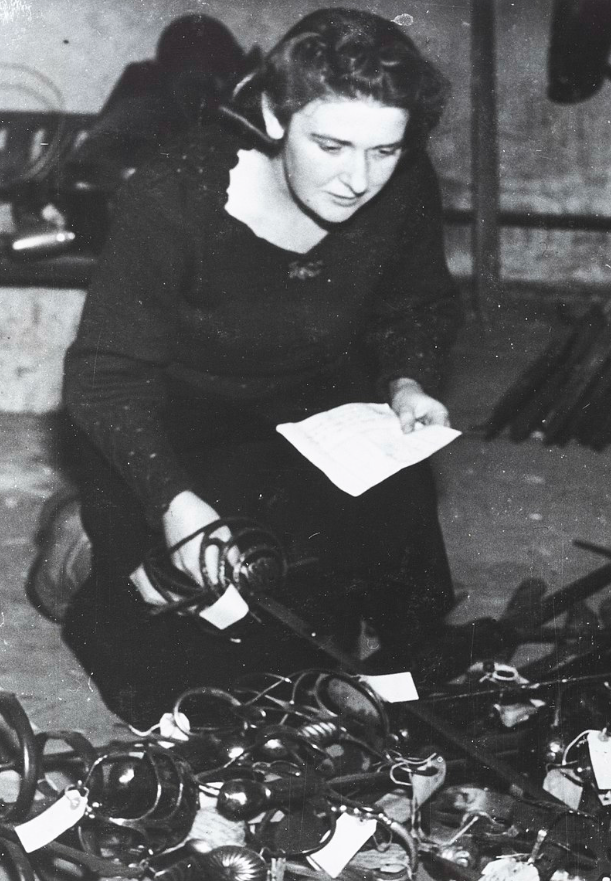

With the outbreak of war, most of the men in York were called up for military service and York Corporation asked Violet to run the museum (although they didn’t raise her salary).

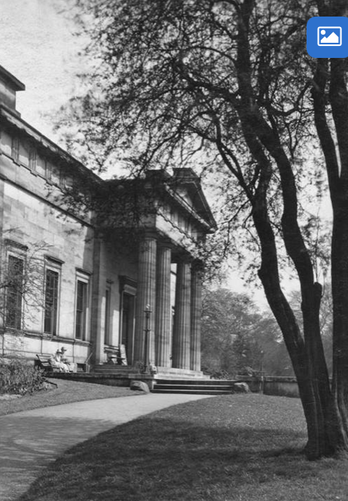

Although, the exhibits at the Castle Museum were unique, Violet recognised that in terms of historical value they didn’t compete with the incredible collection of Roman, Viking, Saxon and pre-historic artifacts at York’s older and more prestigious museum, the Yorkshire Museum. Violet gave up a lot of her free time during the war to help her colleagues at the Yorkshire Museum pack and dispatch their own items to safety.

Thankfully, when York was heavily bombed in 1942 the Castle Museum was spared – although the Yorkshire Museum was hit.

In 1945, when the men returned from war, the corporation appointed a male curator for the museum and gave him twice the money they’d paid Violet.

Naturally disgruntled, Violet married her fiancé, a Polish army lieutenant, Władysław Włoch, and in 1947 she moved with him to Warsaw to continue her career. She became a Curator at the Historical Museum of Krakow and was awarded the Polish Cross of Merit for her work.

Here’s hoping.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed