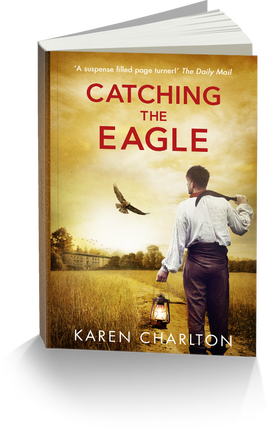

Catching the Eagle

by Karen Charlton

(Based on a true Story)

Easter Monday, 1809: Kirkley Hall manor house is mysteriously burgled. When suspicion falls on Jamie Charlton, he and his family face a desperate battle to save him from the gallows.

|

When £1,157 rent money is stolen from Kirkley Hall, it is the biggest robbery Northumberland has ever known. The owner sends for Stephen Lavender, a principal officer with the Bow Street magistrate’s court in London, to investigate the crime. Suspicion soon falls on impoverished farm labourer, Jamie Charlton, and the unpopular steward, Michael Aynsley.

Jamie Charlton is a loving family man but he is hot-tempered and careless. As the case grows against him, it seems that only his young brother, William, can save him from an impending miscarriage of justice. But William is struggling with demons of his own. Desperate to break free from the tangled web of family ties which bind him to their small community, he is alarmed to find that he is falling in love with Jamie’s wife. |

|

Set beneath the impenetrable gaze of a stray golden eagle whose fate seems to mirror that of Jamie's, Catching the Eagle, this novel is a fictionalised account of a trial that devastated a family and divided a community.

REVIEWS

'Told with gritty realism, Catching The Eagle is a suspense-filled page-turner, which spares nothing in its descriptions of the hardships and injustices suffered by the poor at the turn of the 19th century.

Its ending leaves the reader poised perfectly for the next volume - for which I can hardly wait.'

Kathy Stevenson, The Daily Mail

* * * * *

'It is a rollicking tale full of adultery, drinking, fighting, gambling.

Rich imagery, suspense and some genuinely likeable characters –as well as plenty of murky ones - make this an enjoyable read. Karen is particularly strong at capturing the Geordie dialect and recreating the rural Northumbrian world of the 1800s, where the wealthy lived in comfort and the poor struggled to make ends meet.’

Laura Fraine, Culture Magazine, The Journal (Newcastle)

Its ending leaves the reader poised perfectly for the next volume - for which I can hardly wait.'

Kathy Stevenson, The Daily Mail

* * * * *

'It is a rollicking tale full of adultery, drinking, fighting, gambling.

Rich imagery, suspense and some genuinely likeable characters –as well as plenty of murky ones - make this an enjoyable read. Karen is particularly strong at capturing the Geordie dialect and recreating the rural Northumbrian world of the 1800s, where the wealthy lived in comfort and the poor struggled to make ends meet.’

Laura Fraine, Culture Magazine, The Journal (Newcastle)

Catching the Eagle

by

Karen Charlton

PROLOGUE

February 1809

A stray eagle flew east over the Cumberland border during that bitterly cold winter of 1809.

Drifting on the icy wind, which slid relentlessly down from the hill country, it soared over a vast expanse of dark and empty beauty. For several days it glided over the silent Northumbrian borderlands; its huge shadow caressed the ruined walls of crumbling castles and the creaking, rotting stumps of ancient gibbets. The eagle plucked unsuspecting prey from the bleak, snow-covered fells and drank from remote rocky waterfalls dripping with icicle daggers.

Now, with the north wind behind it, the golden raptor sailed down into the more sheltered valleys. It drifted unobserved over squat hamlets shrouded in pearly mist where penned animals lowed and bleated hungrily through the damp morning fog.

Finally, it glided towards a copse of towering oaks near Ponteland where it landed, with barely a rustle, in the topmost branches of a tree. Gathering in its vast wings, it groomed its breast feathers and settled down to rest. Its golden eyes flicked warily onto the labourer’s cottage below.

A tall man stooped and came out of the cottage doorway, his face lined with worry and tinged with malnutrition. Jamie Charlton pulled his threadbare coat tighter around his large frame and shivered as he gazed moodily into the distance.

His wife, Priscilla, followed him out into the freezing morning air clutching a shawl over her thin shoulders. Her nightgown billowed around her legs and her dishevelled, auburn hair glinted like fire in the weak morning sunlight. She touched her brooding husband gently on his arm and handed him the blue neckerchief he had forgotten.

His face erupted into a wide grin. He grabbed his wife by the buttocks and pulled her laughing into his arms. Their lips met. For a long time, they stood there locked into their warm embrace. Her long fingers reached out and tenderly stroked the back of his thick thatch of greying, dark hair. Eventually, he tore himself away and then stepped out towards Ponteland over the frozen, black ground.

Shivering, Cilla pulled her woollen shawl tighter around her shoulders. Her own face was now etched with worry. She watched him disappear into the darkened wood before returning to the cottage and her stirring children.

Thirty feet above her, the great eagle fell into a deep and lengthy sleep.

The king of birds: nestling next to the home of one of the poorest men in England.

CHAPTER ONE

Easter Monday, 3April 1809

A dense, white mist enveloped Kirkley Hall at dawn and stubbornly refused to lift. Condensation dulled the leaded window panes which stared blindly across the front lawns. The birds sat mute amongst the damp, drooping leaves of the trees and hedgerows while indiscernible cows lowed in the fields encircling the elegant Hall. At the rear of the building a towering Lebanese cedar glistened with moisture, stretched out and disappeared entirely into the mist above.

Beneath the heavy, creaking boughs of the great tree, dozens of tenant farmers emerged out of the damp gloom, like ghosts. The new arrivals startled those who were leaving. Some came on foot, their boots and the hems of their coats clarted with thick, brown mud; others rode into the courtyard, stinking of wet horse. They knocked in turn at the estate office door and sought audience with the steward in the office upstairs. With grimy hands and blackened fingernails they handed over their half-yearly rent money to Michael Aynsley and his son - who counted, recounted and recorded it carefully.

Aynsley took their money with a face as hard and rugged as a limestone outcrop. He glared at the tenants with disgust and distrust; noting any lack of deference and every missing groat. When his steel-grey eyes scanned the motley group of before him, he saw a shabby, ill-fed crowd of drooping shoulders and averted eyes. Beneath the grime, they looked pale and unhealthy following a hard winter of poor nutrition and scant sunlight.

There were a few though, for whom living in that harsh landscape was more profitable. For them, rent day was a chance to socialise and catch up with the local news. These richer tenants swung themselves down from their horses and traps and strode confidently into the steward’s office. After handing over their money, they chatted amiably with Aynsley about the price of corn and beef and the great eagle which had been seen circling in the skies above the parish.

By four o’clock most of the rent had been collected and Aynsley and his son relaxed and ate a meal of bread, cheese and pickle swilled down with beer. The gloom outside made the office unnaturally dark. Apart from the glowing embers of the fire, a little light came from a few spluttering wax candles on the mantelpiece and the flickering oil lamps which stood in the two oak panelled alcoves on either side of the fireplace. Spare quills, parchment and ledgers lay abandoned. As the Aynsleys shuffled on the stiff-backed chairs, a dog slept peacefully on the flagstones at their feet.

The steward finished his beer and belched loudly. The ale dribbled in thin streams out of the corners of his mouth onto his shaggy beard. He wiped away these beads of moisture with his jacket sleeve and pushed back the thick mane of greying hair which framed his frown.

‘One thousand, one hundred and fifty seven pounds, thirteen shillings and sixpence,’ Aynsley said, unable to hide his admiration for the piles of gleaming coins and stacked bank notes on the ink-stained table. ‘Nathaniel Ogle must be bowlegged with all this brass. Over one thousand pounds for half a year’s rent to keep him in the bloody lap of luxury.’

His son nodded in agreement.

‘Aye, Da. And this is only one of his estates. The man must be rolling in money.’

‘He is rolling in money,’ Aynsley snapped. ‘He’s kept in feather beds, lace and fine French brandy by the likes of us.’

His coarse fingers smoothed down a pile of crackling bank notes.

‘What wouldn’t I give to have this much money?’ he sighed.

‘You’ve done all right, though, Da.’

‘Aye, but I’ve worked damned hard for it, lad. Seven days a week, every week of the year, I’ve dragged myself out of bed to toil on Ogle’s bloody farms. Aye, Sir. Nay, Sir. Anything you want, your bloody Lordship.’ The permanent frown on Aynsley’s face deepened.

‘Why - it was only when I left Home Farm to become steward here - at Kirkley - that I got to lie a-bed on Sundays,’ he continued bitterly. ‘And even then only until eight in a morning; for as steward I now had to chivvy the bloody workforce into his damned chapel. It’s easier to get these stupid heathens to work than it is to get them to prayers.’

‘He’s a good man though, Da…he was right concerned when Ma was dying,’ Joseph pointed out. ‘He prayed for her, regular, like.’

Aynsley shrugged.

‘She still died, didn’t she?’

He sighed, belched and took up his quill again. All four of his sons were far too soft in his eyes - the whole lot of them. The only one of his children with any flint in them was his daughter, Sarah – and what use was that in a woman? But soft or not, his lads were the only people in this Godforsaken parish whom he could trust. He had learnt the hard way about Nathanial Ogle’s chapel going tenants.

‘Right,’ he growled. ‘What’s the full amount again? I’ll enter it into the ledger and write a note to his Lordship.’

‘One thousand, one hundred and fifty-seven pounds, thirteen shillings and sixpence - It’s slightly down on the last yearly amount, mind.’

‘That’ll be because of the two empty cottages in Ogle and the empty farm in Newham,’ muttered Aynsley.

His quill scratched irritably across the page.

‘I must see about getting that farm let. We should put up the rent as well.’

‘What happened to the old farmer? Bates, wasn’t it?’

‘Heddon Poor House,’ Aynsley replied sharply. ‘Him and his wife. No family to take care of them when they got too old.’

He paused meditatively and a wry smile lifted the edges of his moist lips.

‘Not like me, eh? I’ve got you to look after your old Da. Don’t forget, lad, when I’m drooling and pissing myself in my dotage – I want to do it in front of the comfort of your hearth.’

‘There’s a good few years left in you yet, Da.’ Joseph murmured, as he tried to hide his grimace. ‘And there’s always our Sarah’s.’

“Huh! I fancy a bit of peace in me old age – and no man gets any peace living with our Sarah – not even that fancy husband of hers.’

Joseph was not listening. He was distracted with the figures in the ledger before him and scratched his head in confusion.

‘I see Old Henry Dodds over at Wharton hasn’t paid the full amount again.’

His father laughed unpleasantly and took another swig of his beer.

‘Don’t you worry yourself about Old Henry Dodds. We have an agreement, like.’

‘What sort of an agreement?’

Aynsley paused for a moment and eyed his son shrewdly. Then he pushed the chair back and strode casually towards the stone fireplace across the dirty, wooden floorboards. The dog scampered out of his way and slunk off into a corner. He placed his hands onto the edges of the mantelpiece, leaned forward and stared down at the fire.

‘I’ve brought you in this time, son, to show you how a steward’s job is done. One of the ways I do it is that I let Old Henry Dodds pay part of his rent in kind.’

‘In kind? What could Old Henry Dodds have that Mr. Ogle would want?’ Joseph stared in confusion at his father.

Aynsley’s leering grin now stretched from ear to ear.

‘Dodds has a young, and very comely, second wife whom he finds he cannot satisfy.’

‘So Mr. Ogle swives with her?’ Joseph was startled.

‘Not him – you fool,’ Aynsley growled, his face contorted into a lascivious smile. ‘Nathanial Ogle recites psalms and prays for forgiveness for his lust before mounting his own wife. Do you really think he’d be off riding someone else’s?’

‘Why, Da! You dirty old bugger!’ In the dim light from the spluttering candles, Aynsley could see his son blushing.

‘Ye should not mock the idea, Joe – especially if you fancy being steward, one day. It’s a perk of the job, like,’ Aynsley laughed crudely. ‘You ought to ride out with me next week, when I go up to Wharton to collect the ‘outstanding rent.’ Dodds has also got a very bonny daughter – just coming up to fourteen – ripe for the plucking.’

‘Aye, maybe so,’ his son said, wryly. ‘But some of us still have jealous wives. Besides which, how long have you been swiving with Dodd’s missus? Their daughter could be my bloody sister.’

Aynsley threw back his great, shaggy head and roared with laughter. The firelight threw the profile of a rampart lion onto the flaking walls. Joseph laughed too - but nervously. His father’s lechery hovered like an unwelcome spectre between them.

There was a sharp knock at the door. Their laughter ceased abruptly. Aynsley stood up straight and resumed his customary frown.

‘Come in!’

Jamie Charlton stooped and entered the room. A chill draft lifted the edges of the parchment on the table. The big labourer wore a grey carpenter’s apron over his old coat and a frown across his broad face. Tension walked into the room with him.

‘What the bloody hell do you want, Charlton? I sacked you years ago,’ snarled Aynsley.

‘Begging your pardon, like, I need to measure how much wood is needed for the new sash window.’

‘What are you talking about man?’ barked Aynsley. ‘Measuring windows? You drive the bloody cattle to market - you’re a cattle drover. Or at least you were, until I sacked you. What window? What bloody wood?’

Jamie pointed to the hessian bag of tools was slung over his shoulder and the various hammers and chisels, which poked their handles out from his pockets.

‘It is the instructions of Mr. Archibold, the carpenter. I’m assisting him in his work today.’ His blue eyes glistened with thinly-veiled hatred.

‘I’d heard tell that he was lodging with you and your missus over in Milburn,’ said Joseph Aynsley. ‘Giving you some work, is he?’

‘Aye.’

‘You asked Archibold to strengthen this window frame last month,’ Joseph reminded his father. ‘It’s rotten.’

‘Did I? Well, he picks a bad bloody day to choose to get around to it. I’ll have to have words with Archibold. Get on with measuring it then, Charlton, and stop your gawping. Pass me those moneybags, son – and the chest. Let’s get this money put away.’

He strode over to the table and pushed the pewter plates with the remains of their food to one side. The two Aynsleys began to gather up the hundreds of coins from the old table.

Jamie paused and watched. He had never seen anything like it. The glimmering reflection of the gold, silver and burnished metal mesmerised him. The money glinted seductively in the fire light. Golden guineas, silver seven shilling pieces, crowns and half crowns, nickel sixpences and copper three penny bits all dropped tantalisingly out of view into the money sacks. Metal chinked softly on metal. Each piece flashed more brilliantly than the last. He gazed longingly at the money. Transfixed.

Aynsley glanced up and caught the look on his face.

‘I said stop your gawping!’

Startled, Jamie lurched back to reality.

‘I’ll come back later,’ he stammered and walked towards the door.

‘Move it, man!’ Aynsley roared. To emphasise his displeasure, he leapt across the room and aimed a vicious kick at Jamie’s retreating backside. He missed – but his boot caught the back of Jamie’s thigh and knocked the labourer off balance.

Jamie lurched forward and half-fell, half staggered, down the narrow wooden staircase into the store room below. He gritted his teeth and muttered a strangled curse.

Back outside, in the swirling fog and the gloom, he rubbed his sore leg and damned Michael Aynsley to hell. As the pain gradually subsided, he leaned back against the clammy wall, closed his eyes and indulged in a furious fantasy of revenge. He imagined what it would feel like to grind the steward’s bloodied head beneath his boot into the cobbles and horseshit of the yard.

Darkness was falling at five o’clock, when Mr. Archibold, the elderly carpenter, left Kirkley Hall. He packed his treasured tools into his bag, lit his clay pipe and set off cheerfully for his lodgings at Charlton’s cottage. The wisps of silvery smoke from his pipe gently merged into the swirling mist.

Jamie didn’t finish until after six o’clock. He’d managed to avoid Aynsley for the rest of the afternoon and stayed behind to complete his other work after the carpenter had left. Although his thigh still ached, his good humour returned and was heightened by the fact that he now had some money in his pocket to spend at the card tables in the smoky, warmth of the coaching inn at Newhamm Edge. As he half strolled, half limped past the dripping water pump in the yard, the oyster grey day turned into darker gunmetal. Jamie quickened his step as the card tables beckoned.

Forty minutes later Aynsley and his son left the estate office. Their lanterns cast muted shadows across the cobbles in the darkness. Carefully, Aynsley inserted the iron key into the door lock and mindful of the vast amount of money which lay hidden inside, he double-checked to make sure the door was secure.

He paused to chat briefly to his son and to cast a lecherous eye over the soft curves of a passing housemaid. He made a mental note to try and trap her in the laundry room the next day.

Then the two men parted. The younger Aynsley took his lantern, side-stepped the piles of dung which littered the yard and departed on foot through the muddy gloom towards the warmth of his own hearth and wife. The dog padded behind him.

The steward went to the stables where the groom had already prepared his horse. He swung into the saddle and minutes later, he clattered noisily across the cobbles - also on his way to Newhamm Edge.

His arrangement with Nathanial Ogle was to send his employer a letter as soon as the rents were collected and to deposit the money in the bank in Newcastle the next day. The letter lay crushed in the inside pocket of his coat. Part of it read:

‘…the rents have been collected and the bags of gold and silver, along with the rolls of notes are in the wooden chest hidden behind the secret panel. The devil himself could never find it.’

As Aynsley raced into the cobbled courtyard of the coaching inn, the south-bound mail coach was already waiting. The livery stable hands were unhitching the steaming horses. In the shadows beyond the flickering light cast by the lanterns, fresh beasts waited to take their place. The blacksmith was shutting down his forge for the night and one of the parish beggars lay across a doorway, a drunken heap of stinking rags. Servants and porters bustled around the coach; they struggled with the heavy trunks and valises.

The innkeeper stood on the small flight of muddied steps which led into the inn, barking out orders. His massive frame and huge, bushy sideburns filled the doorway. He nodded courteously to the steward and instructed a barmaid to fetch Aynsley a tankard of ale. The steward joined the landlord and watched the passengers scramble back onto the coach.

Their pace quickened to an ungainly scuttle as the rumour spread that the vehicle was overbooked. Nobody wanted to travel on the outside, through an area known to be infested with nocturnal highwaymen. The murdering bands of border reivers may have vanished into the mists of time but Ponteland was still a dangerous place.

Aynsley laughed aloud at the plight of a fat, tightly corseted woman who struggled to board the coach with her short legs and swaying, hooped dress. But nothing was allowed to delay the departure of the mail coaches. Two servants grabbed her opulent rear and propelled her inside in an undignified flurry of lilac satin, peacock feathers and hat boxes. Another servant tossed up her yapping Pekinese.

Then the drivers appeared, refreshed from their suppers in the warm interior of the inn. Swathed in thick, leather coats, fingerless gloves and felt hats against the bitter cold which killed so many of their fellows, the drivers were muffled up to their eyeballs in scarves. They strode purposefully towards the coach and hung lanterns on the outside of the vehicle. After climbing up onto their seats, one of them put Aynsley’s letter into the leather bag which rested between them.

A hush fell over those assembled, as one of the drivers took out a blunderbuss and cocked it ready for firing. Next he took up his coiled post horn and blew. The blast was ear piercing. Beside him, the driver thrashed at the reins and yelled to the horses. The drunken beggar awoke with a scream.

The coach jolted into action, glided around and rumbled seamlessly through the narrow arched exit to the courtyard. The swaying light from its rear lantern soon disappeared into the persistent mist.

His duty done to his employer, Aynsley now thought of the pleasures which were promised him in the warm bed and between the plump, open legs of his mistress: Lottie MacDonald of Stamfordham. He swung himself back into the saddle of his horse and clattered out of the courtyard.

Through the dirty, mullioned window of the inn, Jamie Charlton glared moodily after the steward. He was fuddled from the brandy and a lack of food and his money was nearly all gone. The deep-seated hatred he held for Aynsley surged back through him with a vengeance. He seethed with resentment over today’s latest humiliation at the end of the man’s boot. The desire to waylay the steward in the gloom, knock him off his horse and smash his eyeballs into the back of his skull with a carpenter’s hammer was overwhelming.

Eventually, he sighed, shoved the steward out of his mind and tried to find solace in his favourite pastime. He pushed the last of his coins into the centre of the table.

‘Deal us another hand, Tom,’ he said to one of his fellow card players. ‘Give us a chance to win it back, eh?’

Over at Kirkley Hall, the gloom had thickened; the only light came from the candles which flickered behind the casement windows of the kitchen and the servant quarters. There was a low hum of voices and occasional laughter as the skeleton staff who manned the hall during the master’s absence settled down to prayers, supper and an hour of relaxation before they retired for the night. The main part of the house remained, as usual, in total darkness; white dust cloths were draped like shrouds across the magnificent furniture, priceless portraits and gilded ornaments.

Just after nine, a footman took a spluttering candle around the ground floor of the hall. His footsteps echoed eerily in the deserted building. With his itchy wig tucked beneath his arm, he checked everything was secure and tested the huge bolts on the doors.

Eventually, the laughter ceased and the conversation became interspersed with yawns. Candles were extinguished as the staff drifted off to their attic quarters to settle down for the night. The only sounds now were those of muted snoring, distant sheep and a tiny owl who hooted softly in the drooping boughs of the magnificent cedar tree.

At the edge of the rear courtyard, a moon-shadow crept silently up towards the estate office door. With the soft ease of familiarity, it climbed deftly onto the ground floor window ledge and then pulled itself onto the flat roof above the storeroom. Hard boots scraped lightly over stone.

The nervous owlet hooted and for a brief moment the phantom paused in response.

A hundred feet above them, a large shadow glided silently across the face of the moon. The golden eagle circled slowly above their heads and landed gracefully in the topmost branches of the cedar tree. There was a flurry of terrified squawking. The other roosting birds screeched and fled. Unperturbed, the raptor drew in its huge wings and watched the human below with sharp, passionless eyes.

Confused, the intruder squatted on the flat roof and paused. He was unsure what had disturbed the creatures in the tree. He waited for a window overlooking the courtyard to be thrown up and some light-sleeping servant to cry out: ‘Who goes there?’

But the event had gone unnoticed in the slumbering manor house. The great tree, with its sharp-eyed observer, settled back down again into silence.

Now the shadowy phantom on the roof moved swiftly. The abrupt crack of shattering glass echoed around the courtyard. The sash window of the office slid upwards.

Then the mysterious figure disappeared into the gloomy interior of Kirkley Hall.

A stray eagle flew east over the Cumberland border during that bitterly cold winter of 1809.

Drifting on the icy wind, which slid relentlessly down from the hill country, it soared over a vast expanse of dark and empty beauty. For several days it glided over the silent Northumbrian borderlands; its huge shadow caressed the ruined walls of crumbling castles and the creaking, rotting stumps of ancient gibbets. The eagle plucked unsuspecting prey from the bleak, snow-covered fells and drank from remote rocky waterfalls dripping with icicle daggers.

Now, with the north wind behind it, the golden raptor sailed down into the more sheltered valleys. It drifted unobserved over squat hamlets shrouded in pearly mist where penned animals lowed and bleated hungrily through the damp morning fog.

Finally, it glided towards a copse of towering oaks near Ponteland where it landed, with barely a rustle, in the topmost branches of a tree. Gathering in its vast wings, it groomed its breast feathers and settled down to rest. Its golden eyes flicked warily onto the labourer’s cottage below.

A tall man stooped and came out of the cottage doorway, his face lined with worry and tinged with malnutrition. Jamie Charlton pulled his threadbare coat tighter around his large frame and shivered as he gazed moodily into the distance.

His wife, Priscilla, followed him out into the freezing morning air clutching a shawl over her thin shoulders. Her nightgown billowed around her legs and her dishevelled, auburn hair glinted like fire in the weak morning sunlight. She touched her brooding husband gently on his arm and handed him the blue neckerchief he had forgotten.

His face erupted into a wide grin. He grabbed his wife by the buttocks and pulled her laughing into his arms. Their lips met. For a long time, they stood there locked into their warm embrace. Her long fingers reached out and tenderly stroked the back of his thick thatch of greying, dark hair. Eventually, he tore himself away and then stepped out towards Ponteland over the frozen, black ground.

Shivering, Cilla pulled her woollen shawl tighter around her shoulders. Her own face was now etched with worry. She watched him disappear into the darkened wood before returning to the cottage and her stirring children.

Thirty feet above her, the great eagle fell into a deep and lengthy sleep.

The king of birds: nestling next to the home of one of the poorest men in England.

CHAPTER ONE

Easter Monday, 3April 1809

A dense, white mist enveloped Kirkley Hall at dawn and stubbornly refused to lift. Condensation dulled the leaded window panes which stared blindly across the front lawns. The birds sat mute amongst the damp, drooping leaves of the trees and hedgerows while indiscernible cows lowed in the fields encircling the elegant Hall. At the rear of the building a towering Lebanese cedar glistened with moisture, stretched out and disappeared entirely into the mist above.

Beneath the heavy, creaking boughs of the great tree, dozens of tenant farmers emerged out of the damp gloom, like ghosts. The new arrivals startled those who were leaving. Some came on foot, their boots and the hems of their coats clarted with thick, brown mud; others rode into the courtyard, stinking of wet horse. They knocked in turn at the estate office door and sought audience with the steward in the office upstairs. With grimy hands and blackened fingernails they handed over their half-yearly rent money to Michael Aynsley and his son - who counted, recounted and recorded it carefully.

Aynsley took their money with a face as hard and rugged as a limestone outcrop. He glared at the tenants with disgust and distrust; noting any lack of deference and every missing groat. When his steel-grey eyes scanned the motley group of before him, he saw a shabby, ill-fed crowd of drooping shoulders and averted eyes. Beneath the grime, they looked pale and unhealthy following a hard winter of poor nutrition and scant sunlight.

There were a few though, for whom living in that harsh landscape was more profitable. For them, rent day was a chance to socialise and catch up with the local news. These richer tenants swung themselves down from their horses and traps and strode confidently into the steward’s office. After handing over their money, they chatted amiably with Aynsley about the price of corn and beef and the great eagle which had been seen circling in the skies above the parish.

By four o’clock most of the rent had been collected and Aynsley and his son relaxed and ate a meal of bread, cheese and pickle swilled down with beer. The gloom outside made the office unnaturally dark. Apart from the glowing embers of the fire, a little light came from a few spluttering wax candles on the mantelpiece and the flickering oil lamps which stood in the two oak panelled alcoves on either side of the fireplace. Spare quills, parchment and ledgers lay abandoned. As the Aynsleys shuffled on the stiff-backed chairs, a dog slept peacefully on the flagstones at their feet.

The steward finished his beer and belched loudly. The ale dribbled in thin streams out of the corners of his mouth onto his shaggy beard. He wiped away these beads of moisture with his jacket sleeve and pushed back the thick mane of greying hair which framed his frown.

‘One thousand, one hundred and fifty seven pounds, thirteen shillings and sixpence,’ Aynsley said, unable to hide his admiration for the piles of gleaming coins and stacked bank notes on the ink-stained table. ‘Nathaniel Ogle must be bowlegged with all this brass. Over one thousand pounds for half a year’s rent to keep him in the bloody lap of luxury.’

His son nodded in agreement.

‘Aye, Da. And this is only one of his estates. The man must be rolling in money.’

‘He is rolling in money,’ Aynsley snapped. ‘He’s kept in feather beds, lace and fine French brandy by the likes of us.’

His coarse fingers smoothed down a pile of crackling bank notes.

‘What wouldn’t I give to have this much money?’ he sighed.

‘You’ve done all right, though, Da.’

‘Aye, but I’ve worked damned hard for it, lad. Seven days a week, every week of the year, I’ve dragged myself out of bed to toil on Ogle’s bloody farms. Aye, Sir. Nay, Sir. Anything you want, your bloody Lordship.’ The permanent frown on Aynsley’s face deepened.

‘Why - it was only when I left Home Farm to become steward here - at Kirkley - that I got to lie a-bed on Sundays,’ he continued bitterly. ‘And even then only until eight in a morning; for as steward I now had to chivvy the bloody workforce into his damned chapel. It’s easier to get these stupid heathens to work than it is to get them to prayers.’

‘He’s a good man though, Da…he was right concerned when Ma was dying,’ Joseph pointed out. ‘He prayed for her, regular, like.’

Aynsley shrugged.

‘She still died, didn’t she?’

He sighed, belched and took up his quill again. All four of his sons were far too soft in his eyes - the whole lot of them. The only one of his children with any flint in them was his daughter, Sarah – and what use was that in a woman? But soft or not, his lads were the only people in this Godforsaken parish whom he could trust. He had learnt the hard way about Nathanial Ogle’s chapel going tenants.

‘Right,’ he growled. ‘What’s the full amount again? I’ll enter it into the ledger and write a note to his Lordship.’

‘One thousand, one hundred and fifty-seven pounds, thirteen shillings and sixpence - It’s slightly down on the last yearly amount, mind.’

‘That’ll be because of the two empty cottages in Ogle and the empty farm in Newham,’ muttered Aynsley.

His quill scratched irritably across the page.

‘I must see about getting that farm let. We should put up the rent as well.’

‘What happened to the old farmer? Bates, wasn’t it?’

‘Heddon Poor House,’ Aynsley replied sharply. ‘Him and his wife. No family to take care of them when they got too old.’

He paused meditatively and a wry smile lifted the edges of his moist lips.

‘Not like me, eh? I’ve got you to look after your old Da. Don’t forget, lad, when I’m drooling and pissing myself in my dotage – I want to do it in front of the comfort of your hearth.’

‘There’s a good few years left in you yet, Da.’ Joseph murmured, as he tried to hide his grimace. ‘And there’s always our Sarah’s.’

“Huh! I fancy a bit of peace in me old age – and no man gets any peace living with our Sarah – not even that fancy husband of hers.’

Joseph was not listening. He was distracted with the figures in the ledger before him and scratched his head in confusion.

‘I see Old Henry Dodds over at Wharton hasn’t paid the full amount again.’

His father laughed unpleasantly and took another swig of his beer.

‘Don’t you worry yourself about Old Henry Dodds. We have an agreement, like.’

‘What sort of an agreement?’

Aynsley paused for a moment and eyed his son shrewdly. Then he pushed the chair back and strode casually towards the stone fireplace across the dirty, wooden floorboards. The dog scampered out of his way and slunk off into a corner. He placed his hands onto the edges of the mantelpiece, leaned forward and stared down at the fire.

‘I’ve brought you in this time, son, to show you how a steward’s job is done. One of the ways I do it is that I let Old Henry Dodds pay part of his rent in kind.’

‘In kind? What could Old Henry Dodds have that Mr. Ogle would want?’ Joseph stared in confusion at his father.

Aynsley’s leering grin now stretched from ear to ear.

‘Dodds has a young, and very comely, second wife whom he finds he cannot satisfy.’

‘So Mr. Ogle swives with her?’ Joseph was startled.

‘Not him – you fool,’ Aynsley growled, his face contorted into a lascivious smile. ‘Nathanial Ogle recites psalms and prays for forgiveness for his lust before mounting his own wife. Do you really think he’d be off riding someone else’s?’

‘Why, Da! You dirty old bugger!’ In the dim light from the spluttering candles, Aynsley could see his son blushing.

‘Ye should not mock the idea, Joe – especially if you fancy being steward, one day. It’s a perk of the job, like,’ Aynsley laughed crudely. ‘You ought to ride out with me next week, when I go up to Wharton to collect the ‘outstanding rent.’ Dodds has also got a very bonny daughter – just coming up to fourteen – ripe for the plucking.’

‘Aye, maybe so,’ his son said, wryly. ‘But some of us still have jealous wives. Besides which, how long have you been swiving with Dodd’s missus? Their daughter could be my bloody sister.’

Aynsley threw back his great, shaggy head and roared with laughter. The firelight threw the profile of a rampart lion onto the flaking walls. Joseph laughed too - but nervously. His father’s lechery hovered like an unwelcome spectre between them.

There was a sharp knock at the door. Their laughter ceased abruptly. Aynsley stood up straight and resumed his customary frown.

‘Come in!’

Jamie Charlton stooped and entered the room. A chill draft lifted the edges of the parchment on the table. The big labourer wore a grey carpenter’s apron over his old coat and a frown across his broad face. Tension walked into the room with him.

‘What the bloody hell do you want, Charlton? I sacked you years ago,’ snarled Aynsley.

‘Begging your pardon, like, I need to measure how much wood is needed for the new sash window.’

‘What are you talking about man?’ barked Aynsley. ‘Measuring windows? You drive the bloody cattle to market - you’re a cattle drover. Or at least you were, until I sacked you. What window? What bloody wood?’

Jamie pointed to the hessian bag of tools was slung over his shoulder and the various hammers and chisels, which poked their handles out from his pockets.

‘It is the instructions of Mr. Archibold, the carpenter. I’m assisting him in his work today.’ His blue eyes glistened with thinly-veiled hatred.

‘I’d heard tell that he was lodging with you and your missus over in Milburn,’ said Joseph Aynsley. ‘Giving you some work, is he?’

‘Aye.’

‘You asked Archibold to strengthen this window frame last month,’ Joseph reminded his father. ‘It’s rotten.’

‘Did I? Well, he picks a bad bloody day to choose to get around to it. I’ll have to have words with Archibold. Get on with measuring it then, Charlton, and stop your gawping. Pass me those moneybags, son – and the chest. Let’s get this money put away.’

He strode over to the table and pushed the pewter plates with the remains of their food to one side. The two Aynsleys began to gather up the hundreds of coins from the old table.

Jamie paused and watched. He had never seen anything like it. The glimmering reflection of the gold, silver and burnished metal mesmerised him. The money glinted seductively in the fire light. Golden guineas, silver seven shilling pieces, crowns and half crowns, nickel sixpences and copper three penny bits all dropped tantalisingly out of view into the money sacks. Metal chinked softly on metal. Each piece flashed more brilliantly than the last. He gazed longingly at the money. Transfixed.

Aynsley glanced up and caught the look on his face.

‘I said stop your gawping!’

Startled, Jamie lurched back to reality.

‘I’ll come back later,’ he stammered and walked towards the door.

‘Move it, man!’ Aynsley roared. To emphasise his displeasure, he leapt across the room and aimed a vicious kick at Jamie’s retreating backside. He missed – but his boot caught the back of Jamie’s thigh and knocked the labourer off balance.

Jamie lurched forward and half-fell, half staggered, down the narrow wooden staircase into the store room below. He gritted his teeth and muttered a strangled curse.

Back outside, in the swirling fog and the gloom, he rubbed his sore leg and damned Michael Aynsley to hell. As the pain gradually subsided, he leaned back against the clammy wall, closed his eyes and indulged in a furious fantasy of revenge. He imagined what it would feel like to grind the steward’s bloodied head beneath his boot into the cobbles and horseshit of the yard.

Darkness was falling at five o’clock, when Mr. Archibold, the elderly carpenter, left Kirkley Hall. He packed his treasured tools into his bag, lit his clay pipe and set off cheerfully for his lodgings at Charlton’s cottage. The wisps of silvery smoke from his pipe gently merged into the swirling mist.

Jamie didn’t finish until after six o’clock. He’d managed to avoid Aynsley for the rest of the afternoon and stayed behind to complete his other work after the carpenter had left. Although his thigh still ached, his good humour returned and was heightened by the fact that he now had some money in his pocket to spend at the card tables in the smoky, warmth of the coaching inn at Newhamm Edge. As he half strolled, half limped past the dripping water pump in the yard, the oyster grey day turned into darker gunmetal. Jamie quickened his step as the card tables beckoned.

Forty minutes later Aynsley and his son left the estate office. Their lanterns cast muted shadows across the cobbles in the darkness. Carefully, Aynsley inserted the iron key into the door lock and mindful of the vast amount of money which lay hidden inside, he double-checked to make sure the door was secure.

He paused to chat briefly to his son and to cast a lecherous eye over the soft curves of a passing housemaid. He made a mental note to try and trap her in the laundry room the next day.

Then the two men parted. The younger Aynsley took his lantern, side-stepped the piles of dung which littered the yard and departed on foot through the muddy gloom towards the warmth of his own hearth and wife. The dog padded behind him.

The steward went to the stables where the groom had already prepared his horse. He swung into the saddle and minutes later, he clattered noisily across the cobbles - also on his way to Newhamm Edge.

His arrangement with Nathanial Ogle was to send his employer a letter as soon as the rents were collected and to deposit the money in the bank in Newcastle the next day. The letter lay crushed in the inside pocket of his coat. Part of it read:

‘…the rents have been collected and the bags of gold and silver, along with the rolls of notes are in the wooden chest hidden behind the secret panel. The devil himself could never find it.’

As Aynsley raced into the cobbled courtyard of the coaching inn, the south-bound mail coach was already waiting. The livery stable hands were unhitching the steaming horses. In the shadows beyond the flickering light cast by the lanterns, fresh beasts waited to take their place. The blacksmith was shutting down his forge for the night and one of the parish beggars lay across a doorway, a drunken heap of stinking rags. Servants and porters bustled around the coach; they struggled with the heavy trunks and valises.

The innkeeper stood on the small flight of muddied steps which led into the inn, barking out orders. His massive frame and huge, bushy sideburns filled the doorway. He nodded courteously to the steward and instructed a barmaid to fetch Aynsley a tankard of ale. The steward joined the landlord and watched the passengers scramble back onto the coach.

Their pace quickened to an ungainly scuttle as the rumour spread that the vehicle was overbooked. Nobody wanted to travel on the outside, through an area known to be infested with nocturnal highwaymen. The murdering bands of border reivers may have vanished into the mists of time but Ponteland was still a dangerous place.

Aynsley laughed aloud at the plight of a fat, tightly corseted woman who struggled to board the coach with her short legs and swaying, hooped dress. But nothing was allowed to delay the departure of the mail coaches. Two servants grabbed her opulent rear and propelled her inside in an undignified flurry of lilac satin, peacock feathers and hat boxes. Another servant tossed up her yapping Pekinese.

Then the drivers appeared, refreshed from their suppers in the warm interior of the inn. Swathed in thick, leather coats, fingerless gloves and felt hats against the bitter cold which killed so many of their fellows, the drivers were muffled up to their eyeballs in scarves. They strode purposefully towards the coach and hung lanterns on the outside of the vehicle. After climbing up onto their seats, one of them put Aynsley’s letter into the leather bag which rested between them.

A hush fell over those assembled, as one of the drivers took out a blunderbuss and cocked it ready for firing. Next he took up his coiled post horn and blew. The blast was ear piercing. Beside him, the driver thrashed at the reins and yelled to the horses. The drunken beggar awoke with a scream.

The coach jolted into action, glided around and rumbled seamlessly through the narrow arched exit to the courtyard. The swaying light from its rear lantern soon disappeared into the persistent mist.

His duty done to his employer, Aynsley now thought of the pleasures which were promised him in the warm bed and between the plump, open legs of his mistress: Lottie MacDonald of Stamfordham. He swung himself back into the saddle of his horse and clattered out of the courtyard.

Through the dirty, mullioned window of the inn, Jamie Charlton glared moodily after the steward. He was fuddled from the brandy and a lack of food and his money was nearly all gone. The deep-seated hatred he held for Aynsley surged back through him with a vengeance. He seethed with resentment over today’s latest humiliation at the end of the man’s boot. The desire to waylay the steward in the gloom, knock him off his horse and smash his eyeballs into the back of his skull with a carpenter’s hammer was overwhelming.

Eventually, he sighed, shoved the steward out of his mind and tried to find solace in his favourite pastime. He pushed the last of his coins into the centre of the table.

‘Deal us another hand, Tom,’ he said to one of his fellow card players. ‘Give us a chance to win it back, eh?’

Over at Kirkley Hall, the gloom had thickened; the only light came from the candles which flickered behind the casement windows of the kitchen and the servant quarters. There was a low hum of voices and occasional laughter as the skeleton staff who manned the hall during the master’s absence settled down to prayers, supper and an hour of relaxation before they retired for the night. The main part of the house remained, as usual, in total darkness; white dust cloths were draped like shrouds across the magnificent furniture, priceless portraits and gilded ornaments.

Just after nine, a footman took a spluttering candle around the ground floor of the hall. His footsteps echoed eerily in the deserted building. With his itchy wig tucked beneath his arm, he checked everything was secure and tested the huge bolts on the doors.

Eventually, the laughter ceased and the conversation became interspersed with yawns. Candles were extinguished as the staff drifted off to their attic quarters to settle down for the night. The only sounds now were those of muted snoring, distant sheep and a tiny owl who hooted softly in the drooping boughs of the magnificent cedar tree.

At the edge of the rear courtyard, a moon-shadow crept silently up towards the estate office door. With the soft ease of familiarity, it climbed deftly onto the ground floor window ledge and then pulled itself onto the flat roof above the storeroom. Hard boots scraped lightly over stone.

The nervous owlet hooted and for a brief moment the phantom paused in response.

A hundred feet above them, a large shadow glided silently across the face of the moon. The golden eagle circled slowly above their heads and landed gracefully in the topmost branches of the cedar tree. There was a flurry of terrified squawking. The other roosting birds screeched and fled. Unperturbed, the raptor drew in its huge wings and watched the human below with sharp, passionless eyes.

Confused, the intruder squatted on the flat roof and paused. He was unsure what had disturbed the creatures in the tree. He waited for a window overlooking the courtyard to be thrown up and some light-sleeping servant to cry out: ‘Who goes there?’

But the event had gone unnoticed in the slumbering manor house. The great tree, with its sharp-eyed observer, settled back down again into silence.

Now the shadowy phantom on the roof moved swiftly. The abrupt crack of shattering glass echoed around the courtyard. The sash window of the office slid upwards.

Then the mysterious figure disappeared into the gloomy interior of Kirkley Hall.