Seeking Our Eagle

Seeking Our Eagle is the perfect, non-fiction companion piece for the Karen Charlton's historical novel, Catching the Eagle. Written with honesty and humour, this factual book tells the remarkable story of how the Charltons shook their family tree until a Regency convict fell out.

|

Illustrated with poignant photographs, Seeking Our Eagle takes us on a fascinating journey back through three hundred years and the turbulent lives of seven generations of their family. A semi-autobiographical romp through the centuries, the book explains how the Charltons first became interested in genealogy and uncovered their history. It reveals the devastating impact of World War One on their family in Marske, their Victorian ancestors’ extensive involvement with the North Eastern Railway Company during its heyday in County Durham and how their Northumbrian family was torn apart by dissention in the eighteenth century.

The author shows how, through a mixture of determination and sheer good luck, they finally stumbled across their Regency skeleton in the closet and then turned Jamie’s sorry tale of injustice into a popular historical novel. |

Illuminating the importance of family in all our lives, Seeking our Eagle is an entertaining and informative read for anyone interested in genealogical research, the social history of the North East and for those writing historical fiction.

REVIEW

Family Tree magazine

Karen Clare, April 2013

Seeking Our Eagle

by

Karen Charlton

(The story of the genealogical research behind the novel, Catching the Eagle.)

CHAPTER ONE

Charlton robbers and raiders –

pre- 17th century

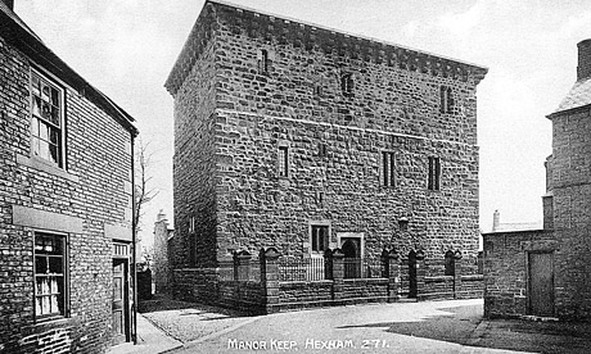

In the heart of a Northumbrian town called Hexham, on an elevated spot above the black and meandering River Tyne, stands a huge, rectangular building known as Hexham Old Gaol. Now a museum, it was the first purpose-built prison in England.

At dusk, it looms out of the twilight like an impenetrable fortress as you trudge up the steep hill from the car park below. The ground floor is a near windowless solid wall of rough-hewn, ancient stone laid several feet thick. Erected in the early 14th century, Hexham Old Gaol was used as a prison for almost 500 years.

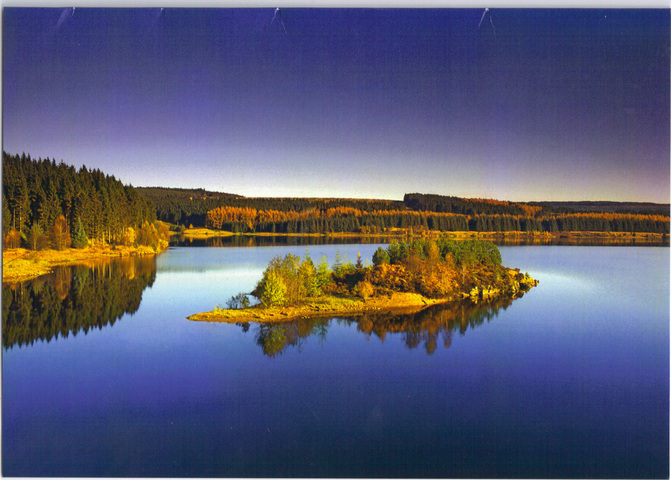

Not many people voluntarily go to prison during their leisure time but in the summer of 1995, we did. My husband, Chris, announced that he wanted to call in and visit this gloomy stronghold on our way up to Kielder in Northumberland. We had set off for a short walking holiday and the car was weighed down with hiking boots, wet-weather gear, a travel cot and the rest of the paraphernalia which goes with a travelling infant and a week’s holiday in the British Isles.

I checked on our sleeping daughter in the back of the car, then stretched out my legs, kicked off my sandals beneath the dashboard and admired the incredible beauty of the rural landscape around us. The sun shone and a vast expanse of ice-blue, northern sky arched above us.

Not many people voluntarily go to prison during their leisure time but in the summer of 1995, we did. My husband, Chris, announced that he wanted to call in and visit this gloomy stronghold on our way up to Kielder in Northumberland. We had set off for a short walking holiday and the car was weighed down with hiking boots, wet-weather gear, a travel cot and the rest of the paraphernalia which goes with a travelling infant and a week’s holiday in the British Isles.

I checked on our sleeping daughter in the back of the car, then stretched out my legs, kicked off my sandals beneath the dashboard and admired the incredible beauty of the rural landscape around us. The sun shone and a vast expanse of ice-blue, northern sky arched above us.

‘Why?’ I asked. ‘Why go to this old prison?’

‘It has a good museum about the border reivers.’

‘Remind me again: who are they?’

Chris turned down the volume on the car CD. Bruce Springsteen faded into the background.

‘The reivers were roving gangs – families - of villains and thieves who terrorised the border region between Scotland and England before the two countries united under James I.’

‘Nice. Mediaeval anarchists.’

He ignored my sarcasm.

‘Every now and then, these families would gather in large numbers, mount their horses and thunder across the border to raid the farms of the Scots.’

‘How did the Scots feel about this?’

Dark sunglasses hid his eyes. I watched him in profile as his strong jawline relaxed and a wide grin spread across his handsome face.

‘They got their own back.’

‘I bet they did.’

‘It was a tough time in history. They were a hard people who lived in harsh times - lawless and violent.’

I glanced at him again, my curiosity piqued. Was he trying to justify this thievery?

‘The two opposing armies of Scotland and England frequently burnt this area to the ground. It reminds me a bit of the American Wild West frontier.’

I smiled. My gentle-giant of a husband clearly romanticised this gang of thugs.

‘The Charltons of the North Tyne Valley were one of the largest of these families of thieves and cattle rustlers.’

‘Humph!’ I teased. ‘My grandmother always said you were a ‘wrong un.’’

This was true. Gladys had been eighty five when she first met Chris. She suffered from dementia and lived in a nursing home. She took one glance at my future husband, declared that he was a ‘wrong un’ and promptly fell back to sleep. I’d gone ahead and married him anyway but it’s not the kind of thing a girl forgets.

‘Anyway, I think this is where my ancestors came from. I’d like to try and find out more about the Charltons from Hexham museum.’

‘But your Dad said your ancestors came from County Durham. They all worked as railway station masters, didn’t they?’

‘Last century, yes,’ Chris explained, patiently. ‘Most Charltons originate from Northumberland. The Charlton reivers lived five hundred years ago.’

I nodded and settled back in my seat. I felt myself relax as the distance increased between us and our humdrum existence of work and child-rearing back in Teesside. Northumberland had always been one of our favourite places in the world. We loved its beauty, its castles and its empty, winding country lanes. The next few days stretched endlessly before us, an exciting blank canvas which we could fill with whatever adventures and experiences we chose. Northumberland smiled and beckoned us towards its turbulent mediaeval history.

Chris’s interest in the Charlton family history had begun when our daughter, Beth, was born and now I was beginning to share his curiosity.

I believe there’s something about having children which not only makes you look forward to the future, but also makes you wonder about where your little one came from. We knew this tiny stranger in our arms was the latest in a long line of Charltons, but who were those shadowy figures in history that had passed down her surname and contributed to her genetic makeup? What were their stories? We wanted to give our children a history which was uniquely theirs.

Of course, to a child, Mum's family is as important as Dad's, but my father had already begun the frustrating job of researching my own family tree. His difficult experiences had made me wary of this genealogy malarkey. My own ancestry heaved with questionable incestuous marriages, several generations of illegitimacy and unexplained name changes. The records showed that our family had roamed south from Norfolk to London then, after a hasty name change, headed sharply north to Lancashire and Yorkshire. My Dad eventually concluded that they were either on the run from the constables or involved in a witness protection scheme. It also appeared that half of them had been abducted by aliens.

In terms of an interesting and unique history, my own ancestry had too many problems and gaps to be considered an enjoyable or suitable story for our children. But no-one at that point had investigated the Charlton line, and despite being an anathema to ardent feminists, the lure and mystery of the traditional, paternal surname is very, very strong.

When Chris and I finally reached Hexham Old Gaol and museum, we found it a fascinating. It gave us a wonderful insight into prison life in medieval times and the era of the border reivers. The interactive exhibits brought them alive.

The Charltons were featured in the museum. They, along with the Milburns, the Robsons and the others, came across as an independent breed of people who didn’t care about anyone or anything not connected to their own tribes. I read about one harassed border official who declared: ‘They are people that will be Scottish when they will and English at their pleasure.’

We learnt that the reivers moved only at night. They took advantage of their intimate knowledge of the remote and rugged terrain, to spirit away their ill-gotten plunder. The two warring governments of Scotland and England were complicit in this state of attrition; it suited them to have gangs of outlaws harassing the enemy on the border. But nobody – not even royalty – dared to travel through this lawless area without armed protection. Apart from robbery, kidnap and blackmail - murder was also common.

I later discovered that the name ‘Charlton’ means ‘free peasant’ or ‘peasant of the free town.’ A ‘free peasant’ was a rarity in a mediaeval England ground down by feudalism. It implies that our surname sprang from a person, or group of people, who refused to accept the rule of their Norman masters. It has also been suggested that the word ‘Charl’ is a corruption of ‘churl’ from churlish. When I combine these two definitions, it evokes a wonderful image of a load of bad-tempered, rebellious yokels, fed up of the constant decimation of their farmland by first one side and then the other, in the continuous war between the Scots and their English overlords. It’s no wonder this area and history created ‘free peasants’ and border reivers.

The peasants revolted, became a law unto themselves and the borderlands became an uncontrollable ‘no-man’s land.’

We scrambled up the stairs to the small room near the top of the gaol. Several ancient tomes lay scattered across a battered, wooden table beneath a glass case. Badly-typed transcripts rubbed shoulders with illegible, original documents. We peered down at close-writ, spidery handwriting and faded ink.

‘Look at this!’ Chris exclaimed. ‘This fellah reckons there were at least six hundred Charlton men ‘without hoss’ who lived in the North Tyne valley in the fourteenth century.’

I padded across to stand next to him and peer in the direction of his pointed finger.

‘What’s a hoss?’

‘Horse.’

‘So, if there were six hundred Charltons ‘without hoss’; how many of them had a hoss?’

‘It doesn’t say.’

My brain began to calculate.

‘If we take into account the women and children – and the men with hosses - there must have been over a thousand Charltons alive in this valley back then.’

I paused for a moment and went to sit down on the uneven window-seat in the thick walls. Behind me the sunlight streamed in through the grimy panes.

‘That’s one hell of a lot of Charltons for just one valley,’ I added, thoughtfully.

‘Yes, and some of them will have been related to us.’ His voice now assumed the smug, velvet tone it always acquired when Middlesbrough F.C. win a football match.

Beth woke up and demanded food. While I gave a bottle of luke-warm milk to the future of the Charltons, Chris continued to wallow in their past. He worked his way round the rest of the old manuscripts.

‘Here’s a good story,’ he informed me over his shoulder. ‘There was a gadgie called Topping Charlton – a notorious law-breaker. They caught him and imprisoned him, here - in Hexham.’

‘Oh, yes?’ I smiled to myself and wondered how many ghosts of his imprisoned ancestors still lingered in this old gaol? It wasn’t a bad place to spend eternity, I decided. It was airy and surprisingly light once you came out of the dungeons. Then Beth gave a cute smile and filled her nappy. Any lingering ghosts bolted for cover.

‘Apparently, the rest of the Charlton boys decided to come and break him out.’ His voice rose with excitement.

‘What happened?’

‘When the gaolers heard that the Charltons had gathered to gallop into Hexham, they fled. They left the gaol unguarded and the reivers rescued Topping without a fight.’

‘Lucky fellah.’ I could see he liked this image of the Charltons men thundering into town to break into the gaol and save one of their own. ‘We’ve come for our boy…’

‘It didn’t end there. A few years later, they recaptured Topping and imprisoned him further away in Berwick castle which was then devastated by the plague. Everyone died except Topping.’

‘How?’

‘I don’t know – it just says that he walked over the dead bodies of his gaolers and out of the open castle gate.’

‘It sounds like he had the luck of the devil.’

‘No, not the devil,’ Chris declared, firmly. ‘He’s one of ours. He had ‘the luck of the Charltons.’’

I smiled. Ever since Chris’ grandfather survived all four years of WW1, his family believe they have a lucky streak.

Just before the museum shut, we clattered back down the wide, stone staircase to the gift shop.

Chris engaged the lady behind the counter in conversation and promptly informed her of our surname.

‘Charltons, eh? Northumberland’s full of ‘em.’ She giggled.

This made sense. Those six hundred men without horses must have had a hobby or two; breeding would probably have been one of them.

Still excited by all our discoveries, we chatted to her for a while about the museum. She helped us choose a framed map of the border region for a souvenir and asked us where we were staying.

‘While yer up at Kielder, yer ought to gan and take a look at Hesleyside.’

‘What’s that?’ I asked.

‘It’s the famous site where the Charlton reivers would gather before they went onto plunder the Scots. It’s bin the home of the leader of the Charlton tribe since the fourteenth century.’

Intrigued, Chris whipped out the maps the minute we arrived back at the car. I began to wonder if we would get to our B&B before dark.

‘It’s all right,’ he reassured me. ‘Look – Hesleyside Hall is on the way to Kielder.’

Fired up with enthusiasm about our ancestral heritage, we found the hall, pulled over and took a few photographs. Built in 1719, the present mansion at Hesleyside occupies the site of a fourteenth century Pele Tower.

‘It has a good museum about the border reivers.’

‘Remind me again: who are they?’

Chris turned down the volume on the car CD. Bruce Springsteen faded into the background.

‘The reivers were roving gangs – families - of villains and thieves who terrorised the border region between Scotland and England before the two countries united under James I.’

‘Nice. Mediaeval anarchists.’

He ignored my sarcasm.

‘Every now and then, these families would gather in large numbers, mount their horses and thunder across the border to raid the farms of the Scots.’

‘How did the Scots feel about this?’

Dark sunglasses hid his eyes. I watched him in profile as his strong jawline relaxed and a wide grin spread across his handsome face.

‘They got their own back.’

‘I bet they did.’

‘It was a tough time in history. They were a hard people who lived in harsh times - lawless and violent.’

I glanced at him again, my curiosity piqued. Was he trying to justify this thievery?

‘The two opposing armies of Scotland and England frequently burnt this area to the ground. It reminds me a bit of the American Wild West frontier.’

I smiled. My gentle-giant of a husband clearly romanticised this gang of thugs.

‘The Charltons of the North Tyne Valley were one of the largest of these families of thieves and cattle rustlers.’

‘Humph!’ I teased. ‘My grandmother always said you were a ‘wrong un.’’

This was true. Gladys had been eighty five when she first met Chris. She suffered from dementia and lived in a nursing home. She took one glance at my future husband, declared that he was a ‘wrong un’ and promptly fell back to sleep. I’d gone ahead and married him anyway but it’s not the kind of thing a girl forgets.

‘Anyway, I think this is where my ancestors came from. I’d like to try and find out more about the Charltons from Hexham museum.’

‘But your Dad said your ancestors came from County Durham. They all worked as railway station masters, didn’t they?’

‘Last century, yes,’ Chris explained, patiently. ‘Most Charltons originate from Northumberland. The Charlton reivers lived five hundred years ago.’

I nodded and settled back in my seat. I felt myself relax as the distance increased between us and our humdrum existence of work and child-rearing back in Teesside. Northumberland had always been one of our favourite places in the world. We loved its beauty, its castles and its empty, winding country lanes. The next few days stretched endlessly before us, an exciting blank canvas which we could fill with whatever adventures and experiences we chose. Northumberland smiled and beckoned us towards its turbulent mediaeval history.

Chris’s interest in the Charlton family history had begun when our daughter, Beth, was born and now I was beginning to share his curiosity.

I believe there’s something about having children which not only makes you look forward to the future, but also makes you wonder about where your little one came from. We knew this tiny stranger in our arms was the latest in a long line of Charltons, but who were those shadowy figures in history that had passed down her surname and contributed to her genetic makeup? What were their stories? We wanted to give our children a history which was uniquely theirs.

Of course, to a child, Mum's family is as important as Dad's, but my father had already begun the frustrating job of researching my own family tree. His difficult experiences had made me wary of this genealogy malarkey. My own ancestry heaved with questionable incestuous marriages, several generations of illegitimacy and unexplained name changes. The records showed that our family had roamed south from Norfolk to London then, after a hasty name change, headed sharply north to Lancashire and Yorkshire. My Dad eventually concluded that they were either on the run from the constables or involved in a witness protection scheme. It also appeared that half of them had been abducted by aliens.

In terms of an interesting and unique history, my own ancestry had too many problems and gaps to be considered an enjoyable or suitable story for our children. But no-one at that point had investigated the Charlton line, and despite being an anathema to ardent feminists, the lure and mystery of the traditional, paternal surname is very, very strong.

When Chris and I finally reached Hexham Old Gaol and museum, we found it a fascinating. It gave us a wonderful insight into prison life in medieval times and the era of the border reivers. The interactive exhibits brought them alive.

The Charltons were featured in the museum. They, along with the Milburns, the Robsons and the others, came across as an independent breed of people who didn’t care about anyone or anything not connected to their own tribes. I read about one harassed border official who declared: ‘They are people that will be Scottish when they will and English at their pleasure.’

We learnt that the reivers moved only at night. They took advantage of their intimate knowledge of the remote and rugged terrain, to spirit away their ill-gotten plunder. The two warring governments of Scotland and England were complicit in this state of attrition; it suited them to have gangs of outlaws harassing the enemy on the border. But nobody – not even royalty – dared to travel through this lawless area without armed protection. Apart from robbery, kidnap and blackmail - murder was also common.

I later discovered that the name ‘Charlton’ means ‘free peasant’ or ‘peasant of the free town.’ A ‘free peasant’ was a rarity in a mediaeval England ground down by feudalism. It implies that our surname sprang from a person, or group of people, who refused to accept the rule of their Norman masters. It has also been suggested that the word ‘Charl’ is a corruption of ‘churl’ from churlish. When I combine these two definitions, it evokes a wonderful image of a load of bad-tempered, rebellious yokels, fed up of the constant decimation of their farmland by first one side and then the other, in the continuous war between the Scots and their English overlords. It’s no wonder this area and history created ‘free peasants’ and border reivers.

The peasants revolted, became a law unto themselves and the borderlands became an uncontrollable ‘no-man’s land.’

We scrambled up the stairs to the small room near the top of the gaol. Several ancient tomes lay scattered across a battered, wooden table beneath a glass case. Badly-typed transcripts rubbed shoulders with illegible, original documents. We peered down at close-writ, spidery handwriting and faded ink.

‘Look at this!’ Chris exclaimed. ‘This fellah reckons there were at least six hundred Charlton men ‘without hoss’ who lived in the North Tyne valley in the fourteenth century.’

I padded across to stand next to him and peer in the direction of his pointed finger.

‘What’s a hoss?’

‘Horse.’

‘So, if there were six hundred Charltons ‘without hoss’; how many of them had a hoss?’

‘It doesn’t say.’

My brain began to calculate.

‘If we take into account the women and children – and the men with hosses - there must have been over a thousand Charltons alive in this valley back then.’

I paused for a moment and went to sit down on the uneven window-seat in the thick walls. Behind me the sunlight streamed in through the grimy panes.

‘That’s one hell of a lot of Charltons for just one valley,’ I added, thoughtfully.

‘Yes, and some of them will have been related to us.’ His voice now assumed the smug, velvet tone it always acquired when Middlesbrough F.C. win a football match.

Beth woke up and demanded food. While I gave a bottle of luke-warm milk to the future of the Charltons, Chris continued to wallow in their past. He worked his way round the rest of the old manuscripts.

‘Here’s a good story,’ he informed me over his shoulder. ‘There was a gadgie called Topping Charlton – a notorious law-breaker. They caught him and imprisoned him, here - in Hexham.’

‘Oh, yes?’ I smiled to myself and wondered how many ghosts of his imprisoned ancestors still lingered in this old gaol? It wasn’t a bad place to spend eternity, I decided. It was airy and surprisingly light once you came out of the dungeons. Then Beth gave a cute smile and filled her nappy. Any lingering ghosts bolted for cover.

‘Apparently, the rest of the Charlton boys decided to come and break him out.’ His voice rose with excitement.

‘What happened?’

‘When the gaolers heard that the Charltons had gathered to gallop into Hexham, they fled. They left the gaol unguarded and the reivers rescued Topping without a fight.’

‘Lucky fellah.’ I could see he liked this image of the Charltons men thundering into town to break into the gaol and save one of their own. ‘We’ve come for our boy…’

‘It didn’t end there. A few years later, they recaptured Topping and imprisoned him further away in Berwick castle which was then devastated by the plague. Everyone died except Topping.’

‘How?’

‘I don’t know – it just says that he walked over the dead bodies of his gaolers and out of the open castle gate.’

‘It sounds like he had the luck of the devil.’

‘No, not the devil,’ Chris declared, firmly. ‘He’s one of ours. He had ‘the luck of the Charltons.’’

I smiled. Ever since Chris’ grandfather survived all four years of WW1, his family believe they have a lucky streak.

Just before the museum shut, we clattered back down the wide, stone staircase to the gift shop.

Chris engaged the lady behind the counter in conversation and promptly informed her of our surname.

‘Charltons, eh? Northumberland’s full of ‘em.’ She giggled.

This made sense. Those six hundred men without horses must have had a hobby or two; breeding would probably have been one of them.

Still excited by all our discoveries, we chatted to her for a while about the museum. She helped us choose a framed map of the border region for a souvenir and asked us where we were staying.

‘While yer up at Kielder, yer ought to gan and take a look at Hesleyside.’

‘What’s that?’ I asked.

‘It’s the famous site where the Charlton reivers would gather before they went onto plunder the Scots. It’s bin the home of the leader of the Charlton tribe since the fourteenth century.’

Intrigued, Chris whipped out the maps the minute we arrived back at the car. I began to wonder if we would get to our B&B before dark.

‘It’s all right,’ he reassured me. ‘Look – Hesleyside Hall is on the way to Kielder.’

Fired up with enthusiasm about our ancestral heritage, we found the hall, pulled over and took a few photographs. Built in 1719, the present mansion at Hesleyside occupies the site of a fourteenth century Pele Tower.

According to the woman in the gift shop, there is a legend that the Charlton reivers would gather here for a drunken feast before they went out on a raid. When the pantry was empty, the lady of the house brought out a spur on a silver platter as a signal to the men to get on their ‘hosses’, set off for Scotland and fetch home the bacon, beef and mutton.

Smitten with the legend, Hesleyside and the whole border reiver heritage, Chris began to daydream he was the long-lost heir of Hesleyside. The romance of the history, the glorious fresh air and the excitement of our discoveries were a heady mixture.

Later that night, after an excellent meal in the pub and a several pints of Guinness, Chris became uncharacteristically bold.

‘I think we’ll return to Hesleyside tomorrow and drive up to the front door.’

I spluttered into my chardonnay.

‘Sorry? What?’

‘We’ll go and introduce ourselves to the Charltons of Hesleyside.’

I stared at him in surprise, stunned by his announcement and slightly appalled by it at the same time. Quiet, polite and shy, Chris had never been prone to harassing total strangers in their own homes before. In fact, he would have made a lousy door-to-door salesman.

‘And what’ll we say to them, exactly?’

He thought for a moment, eyes misted with romance and Guinness.

‘How about: ‘We’re here!’

Fortunately, he sobered up the next day and I persuaded him to leave the Charltons of Hesleyside undisturbed. We abandoned our surprise assault on the hall – for the time being.

Smitten with the legend, Hesleyside and the whole border reiver heritage, Chris began to daydream he was the long-lost heir of Hesleyside. The romance of the history, the glorious fresh air and the excitement of our discoveries were a heady mixture.

Later that night, after an excellent meal in the pub and a several pints of Guinness, Chris became uncharacteristically bold.

‘I think we’ll return to Hesleyside tomorrow and drive up to the front door.’

I spluttered into my chardonnay.

‘Sorry? What?’

‘We’ll go and introduce ourselves to the Charltons of Hesleyside.’

I stared at him in surprise, stunned by his announcement and slightly appalled by it at the same time. Quiet, polite and shy, Chris had never been prone to harassing total strangers in their own homes before. In fact, he would have made a lousy door-to-door salesman.

‘And what’ll we say to them, exactly?’

He thought for a moment, eyes misted with romance and Guinness.

‘How about: ‘We’re here!’

Fortunately, he sobered up the next day and I persuaded him to leave the Charltons of Hesleyside undisturbed. We abandoned our surprise assault on the hall – for the time being.

This trip to the North Tyne valley inspired us.

Everywhere we turned, we found more information about the Charltons and the reiver heritage. By the time we left Northumberland in the summer of 1995, we were desperate to begin our family history research. We wanted to uncover characters like ‘Topping’ and links to Hesleyside and the Charlton reivers. But there were 500 years between us and them and we didn’t have a clue where to start.

Our genealogical research has been a long journey. It has taken us nearly eighteen years to scrape away the fogs of time and inch back through the centuries to 1700. We are still a couple of centuries away from ‘Topping Charlton’ and I doubt that we’ll ever manage to get our line back to the time of the reivers. Much to Chris’s disappointment, I suspect that we’ll never find the evidence to prove him the rightful heir to Hesleyside Hall.

Yet, the stories we have uncovered are more fascinating, amusing and tragic than we could ever imagine. We may not have Topping but we have our convict Jamie and his wife, Cilla. We have ‘Soldier Will’, the tragic Mary Famelton, ‘Stationmaster Will’ and a whole host of dysfunctional Charltons who lived at North Carter Moor farm in the 18th century. I suspect we have dug up enough excitement and salacious gossip to fill another series of historical novels, so perhaps we should be more satisfied.

This is our family history.

Everywhere we turned, we found more information about the Charltons and the reiver heritage. By the time we left Northumberland in the summer of 1995, we were desperate to begin our family history research. We wanted to uncover characters like ‘Topping’ and links to Hesleyside and the Charlton reivers. But there were 500 years between us and them and we didn’t have a clue where to start.

Our genealogical research has been a long journey. It has taken us nearly eighteen years to scrape away the fogs of time and inch back through the centuries to 1700. We are still a couple of centuries away from ‘Topping Charlton’ and I doubt that we’ll ever manage to get our line back to the time of the reivers. Much to Chris’s disappointment, I suspect that we’ll never find the evidence to prove him the rightful heir to Hesleyside Hall.

Yet, the stories we have uncovered are more fascinating, amusing and tragic than we could ever imagine. We may not have Topping but we have our convict Jamie and his wife, Cilla. We have ‘Soldier Will’, the tragic Mary Famelton, ‘Stationmaster Will’ and a whole host of dysfunctional Charltons who lived at North Carter Moor farm in the 18th century. I suspect we have dug up enough excitement and salacious gossip to fill another series of historical novels, so perhaps we should be more satisfied.

This is our family history.